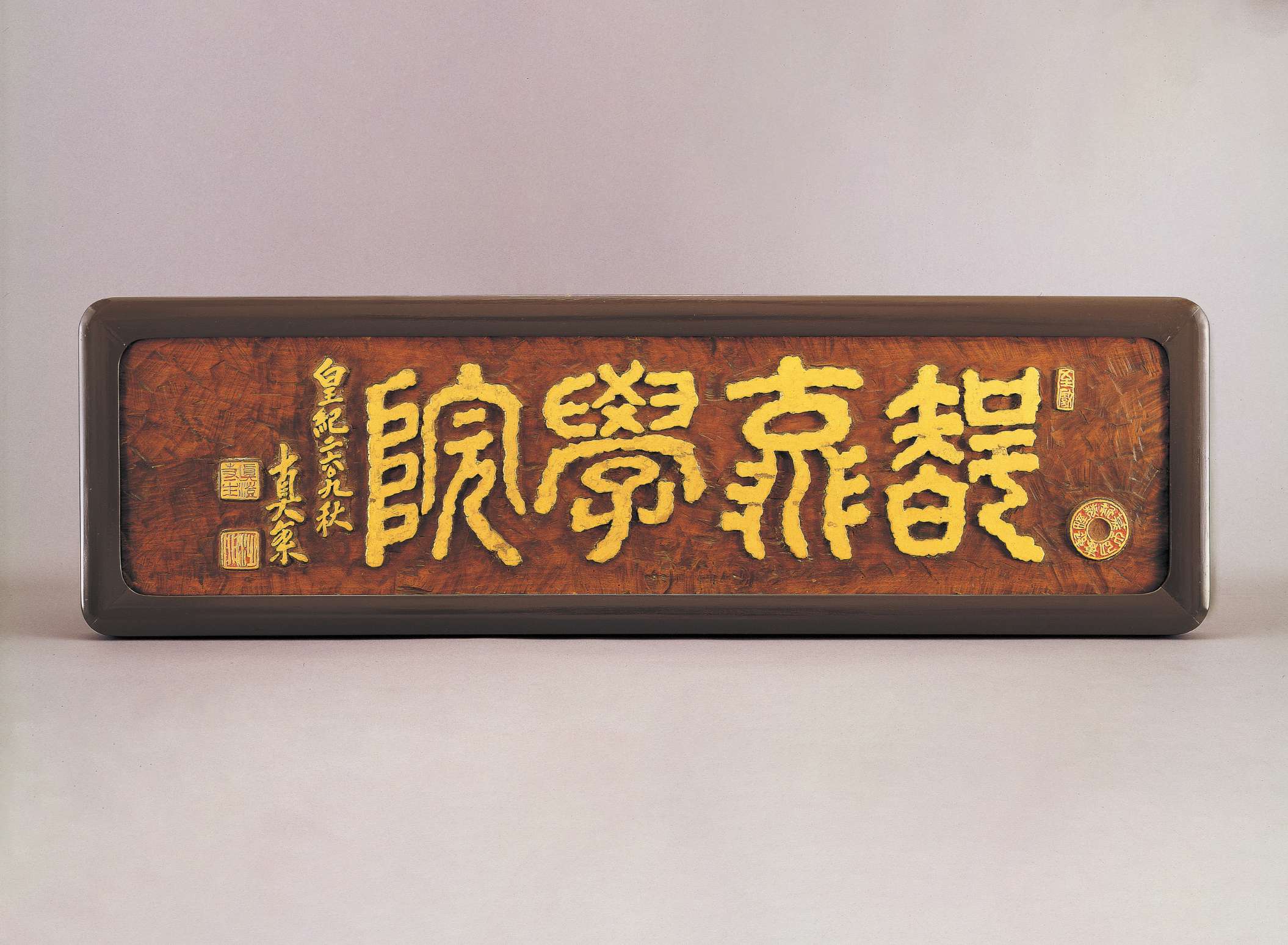

Calligraphy and Engravings

Chiryu Gakuin (“Wisdom-Stream School”)

1 of 15

Engraving, Judas woodDimensions: 37 x 123 cmCa. 1949Chiryu Gakuin is the name of Shinnyo‑en’s dharma school for those aspiring to be ordained as priests. Shinjo opened this facility to train people to become dharma teachers.

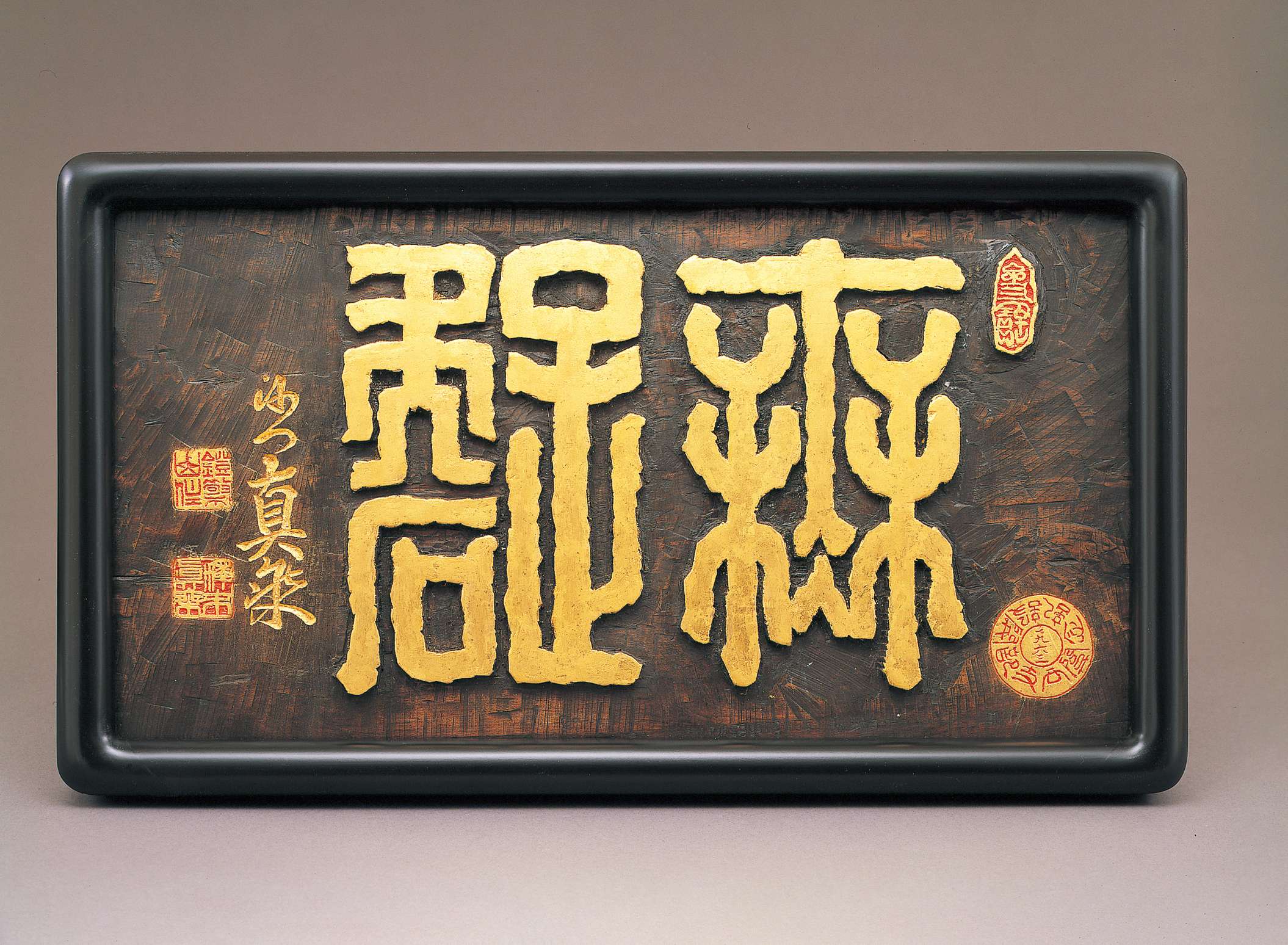

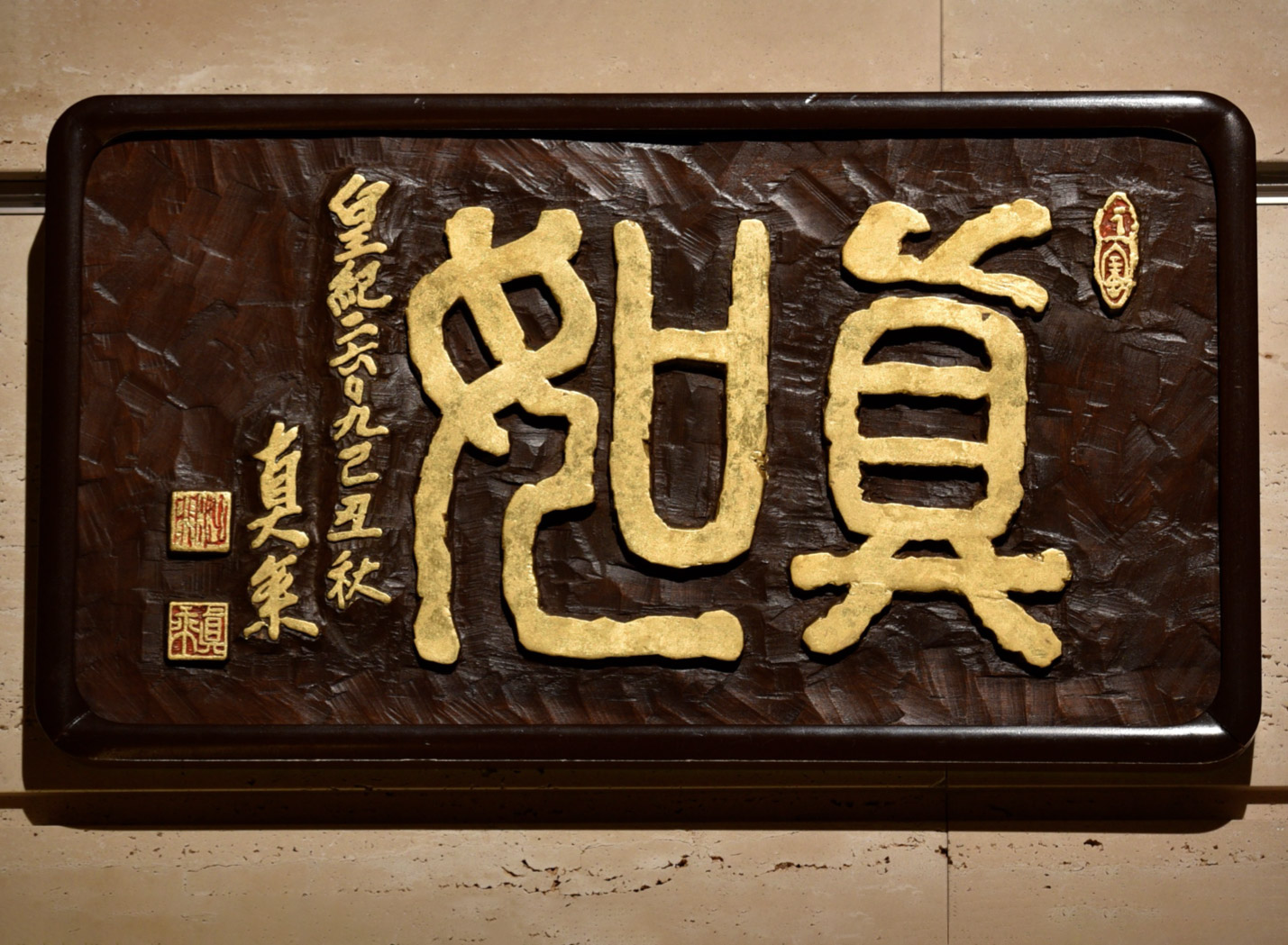

Muge (“Unhindered”)

無碍

2 of 15

Judas woodDimensions: 32.2 x 57.8 cmCa. 1963The word muge means “free of obstacles,” in the sense that underneath conditioned reality there is nothing to prevent one from overcoming any hurdle. Muge reminds practitioners of the path the Buddha took to freedom, of his unfettered mind and courage to let go of attachments, which led to his supreme enlightenment.

Nyoze (“It Is Thus”)

如是

3 of 15

Engraving, Judas woodDimensions: 32.1 x 25.6 cmCa. 1964Nyoze, also read kaku no gotoshi, is a profoundly meaningful expression that loosely translates as “It is thus.” After the death of Shakyamuni his disciples gathered to compile, clarify, and standardize the meaning of what he had taught. The results of such gatherings over the centuries formed the basis for the Pali Buddhist sutras, which began with the words, “Thus have I heard.” This opening line, included in many texts, expresses reverence and respect toward Shakyamuni’s teachings.

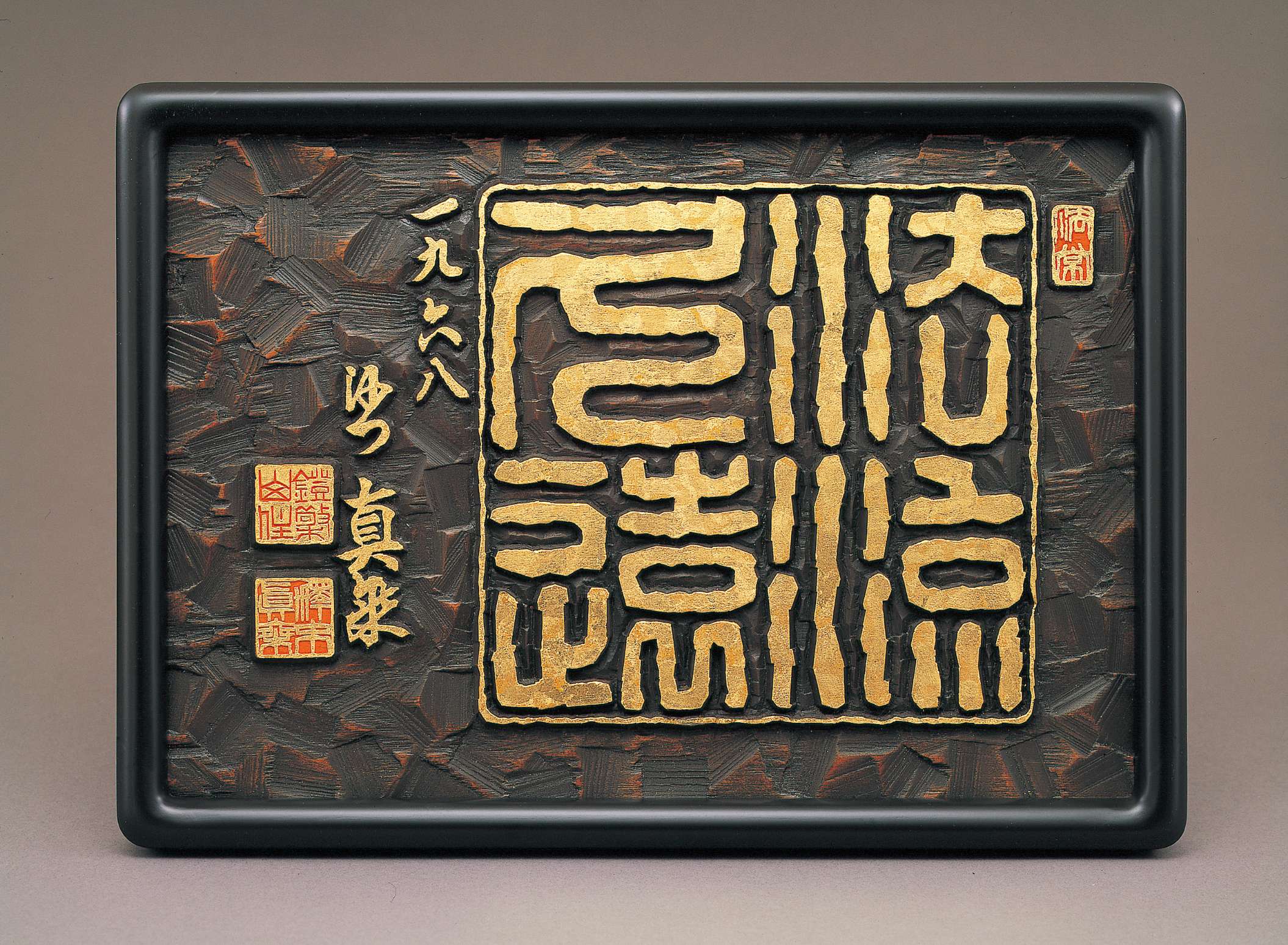

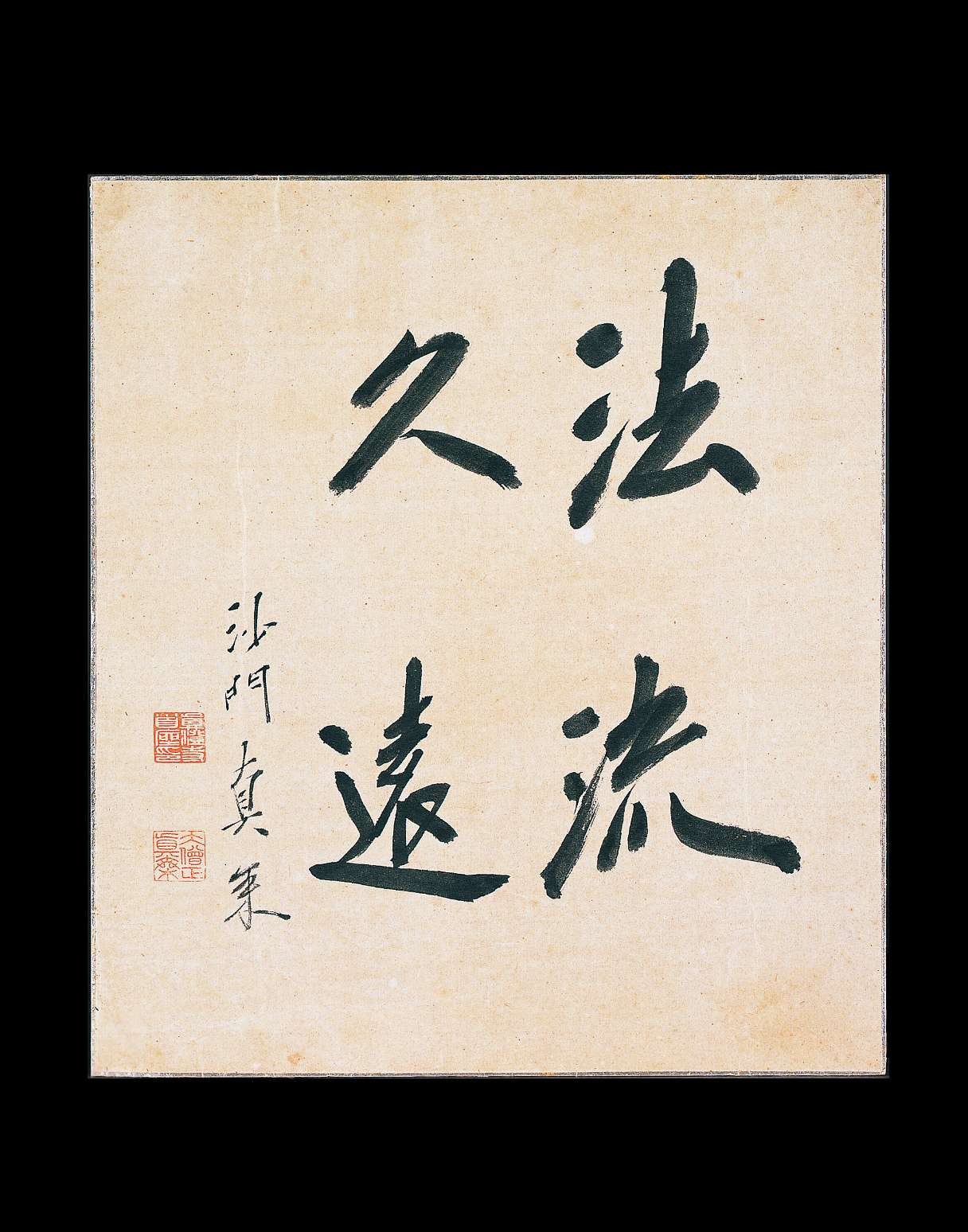

Horyu Kuon (“Eternal is the Dharma Stream”)

法流久遠

4 of 15

Engraving, Japanese Judas woodDimensions: 30.2 x 42.1 cmCa. 1968The term horyu literally means “dharma stream,” that is, the continuous lineage of Buddhist teachers. In the Shingon school of esoteric Buddhism, the dharma practice originating with the Tathagata Mahavairochana has been continually handed down from teacher to disciple for over 2500 years. This method of direct transmission is highly revered in the Shingon faith. Shinjo carved this work in 1968, the year that the new head temple of Shinnyo‑en was consecrated, and the words symbolize his hopes that the chain of transmission will remain unbroken.

Shinnyo

真如

5 of 15

Engraving, Japanese Judas woodDimensions: 30.2 x 42.1 cmCa. 1968Master Shinjo carved this calligraphy of shinnyo in October of 1949. In May 1950, Master Tomoji completed her training and became the first successor of the Shinnyo dharma lineage, receiving the dharma name “Shinnyo.” The “Dharma Crisis,” during which the community was almost destroyed, erupted just three months later. Shinjo, Tomoji, and those who remained in the sangha resolved to overcome the difficulties, and make a fresh start. Shinnyo‑en was the name given that renewal thanks to Shindoin, who used his spiritual faculty to help choose it. This carving later adorned the wall of Shinjo’s study, where he studied the Nirvana Sutra, wrote many articles, and created the prototype for the large Nirvana Buddha image.

Shinnyo Ichinyo (“Oneness with Ultimate Reality”)

真如一如

6 of 15

Engraving, Pine woodDimensions: 59.5 x 158.7 cmCa. 1968The term shinnyo translates as “suchness” and means “underlying nature” or “ultimate reality” as defined by Buddhism, while ichinyo, literally, means “oneness” and refers to the non-dualistic union with universal truth. To this concept, Shinjo added his own spiritual realization that to be one with truth means to behave as one with the spirit of a buddha and work at a practical level for the benefit of all sentient beings. Displayed at the Shinnyo‑en head temple, facing the Great nirvana Image, the engraving is a reflection of the prayers imbued in that central devotional figure.

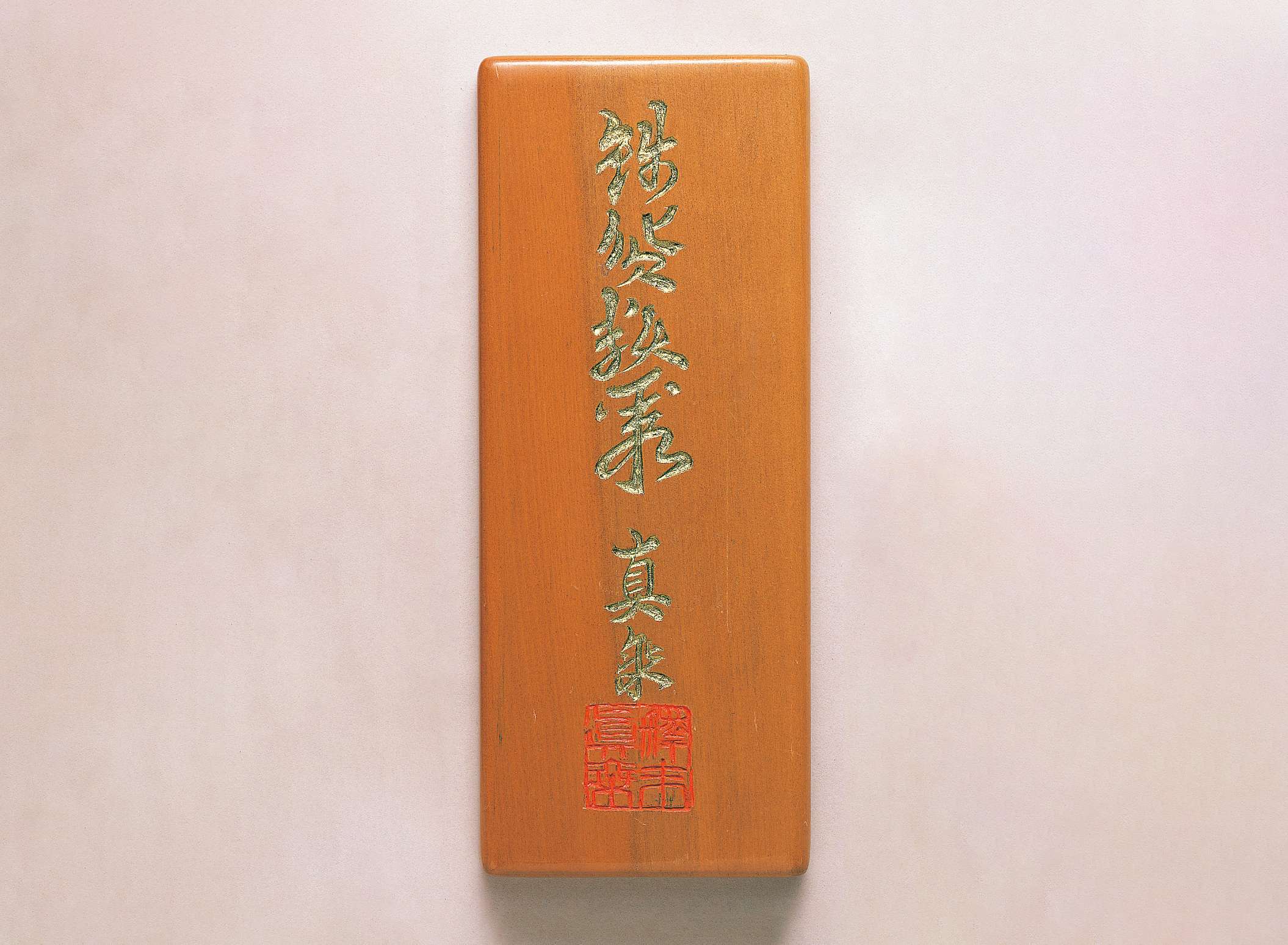

Senka Ruiju (“Collections of Old Coins”)

銭貨類集

7 of 15

EngravingDimensions: 23.6 x 9.6 cmCa. 1962Shinjo carved the inscription senka ruiju on the lid of this box, in which he placed some old coins. Since he believed that some people are afflicted with greed and despair in relation to money, and that this suffering can become a root of misery and unhappiness, he created this way to pray for the alleviation of materialistic worries.

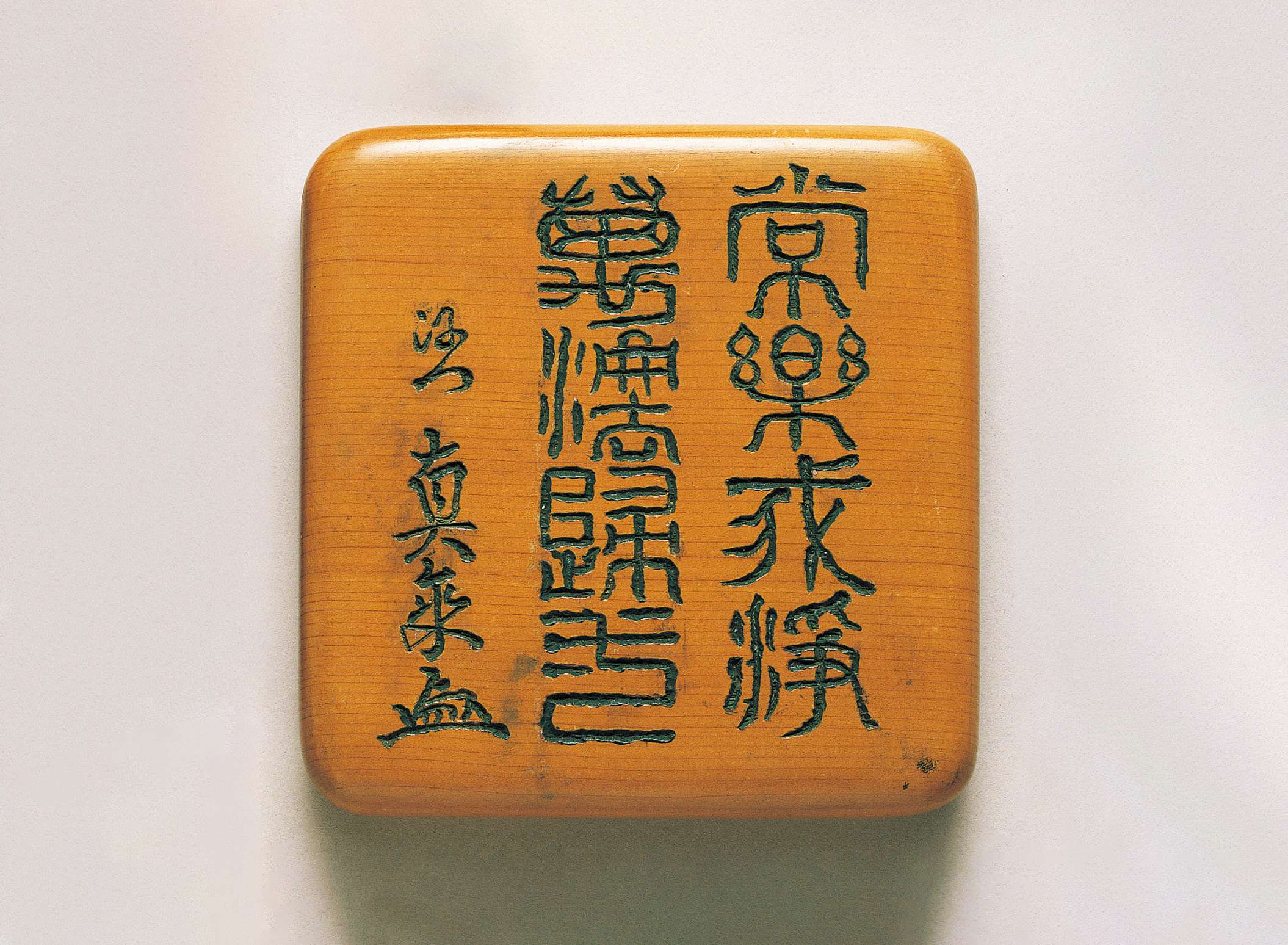

Jo Raku Ga Jo, Bampo Kiitsu (“Permanence, Bliss, Self, and Purity—All Teachings Return to Being One”)

常楽我浄 万法帰一

8 of 15

Engraving, box for divination toolsDimensions: 14.6 x 14.5 cmCa. 1972When Shinjo was in his early teens, his father passed down to him the family tradition of Byozei divination. He went on to hone these skills during his years as an aeronautical engineer, by attending lectures given by the Divination Association of Greater Japan. He received a teaching certification in the art of divination, but remained faithful to his father’s admonition to use his skills only if requested—and never for personal gain. This carving appears on the box in which he kept his divination tools. It is just one of the many engravings found on his wooden items—his inkstone box for calligraphy, the box for his carving tools and whetstone, and so on—that he used in daily life.

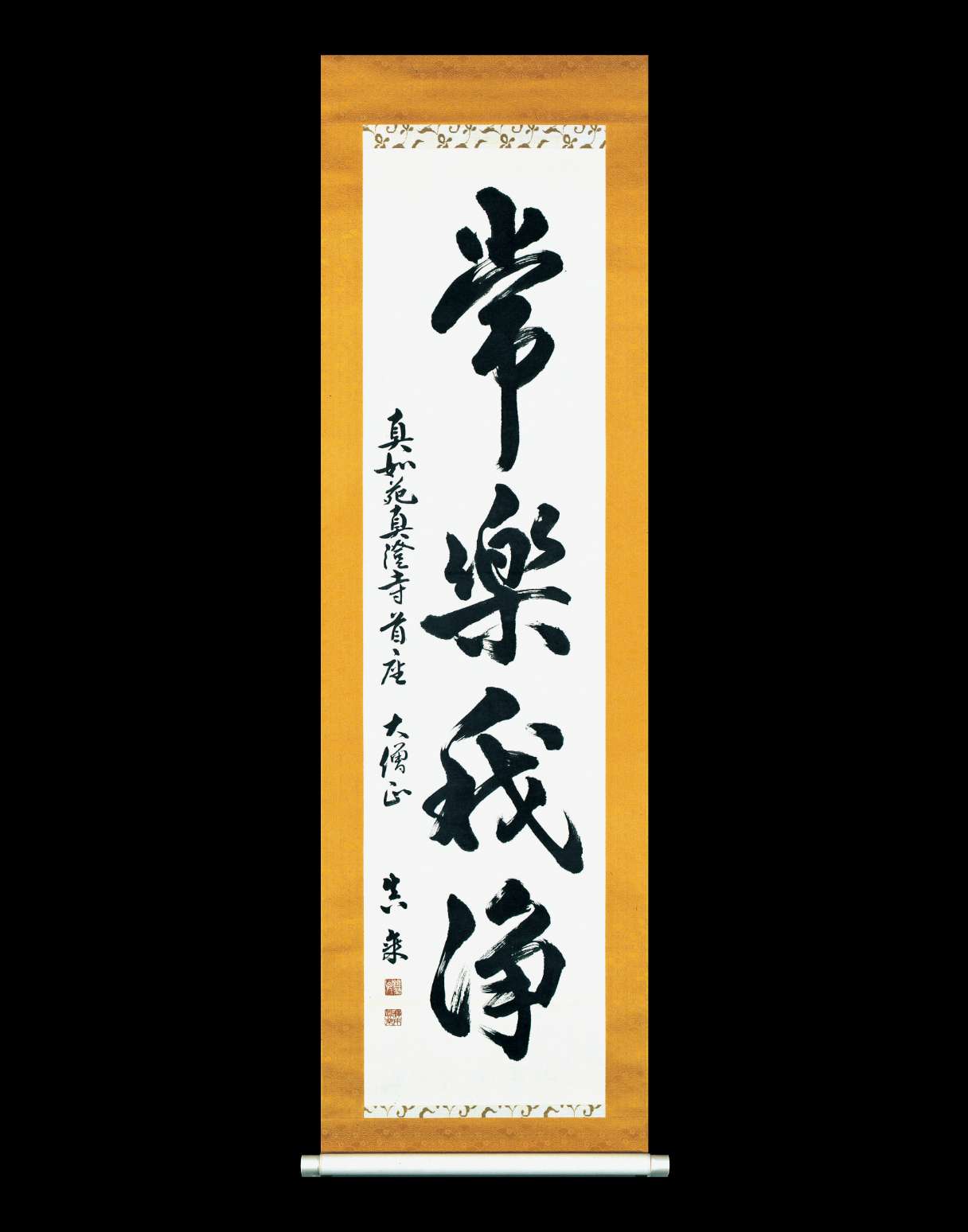

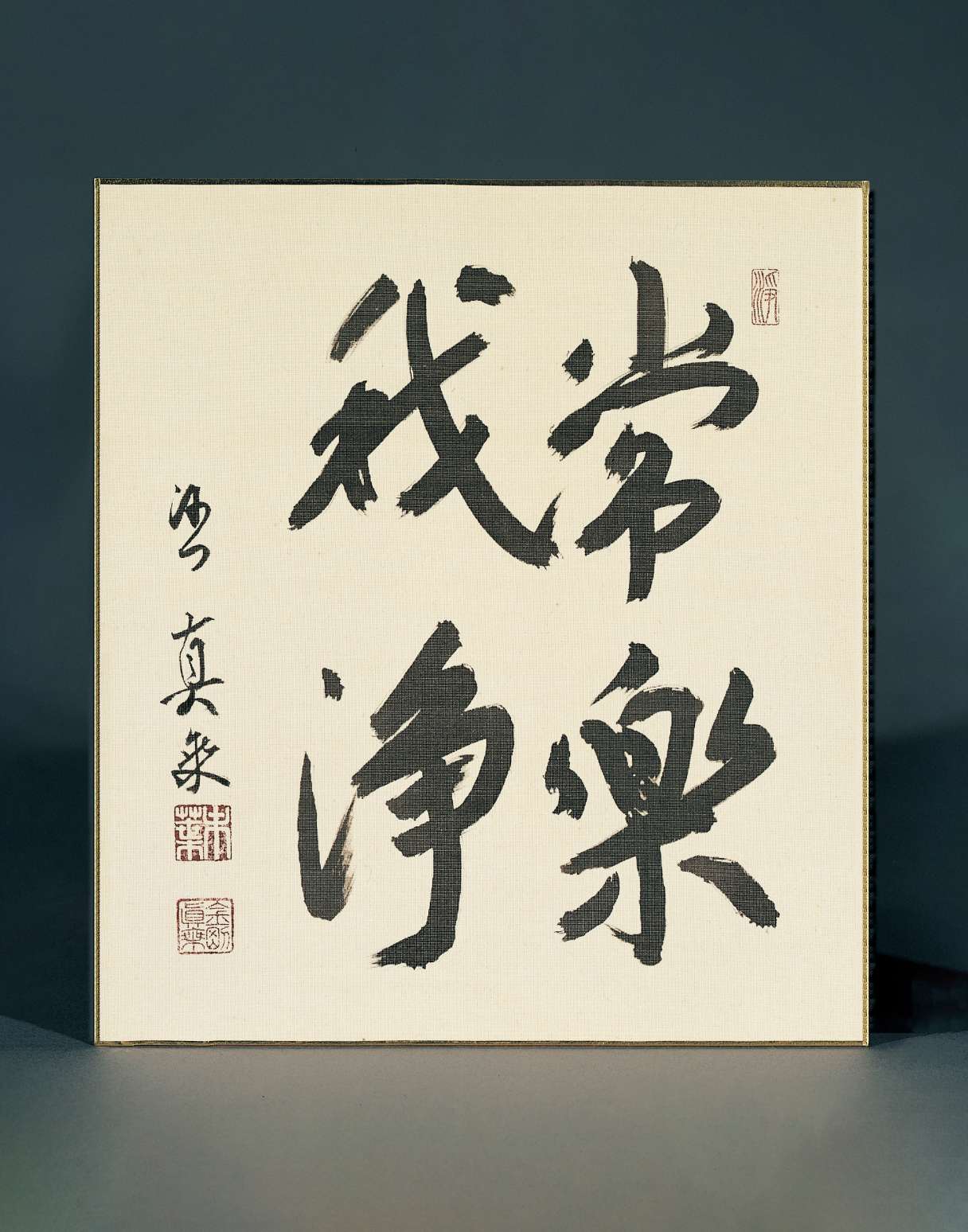

Jo Raku Ga Jo (“Permanence, Bliss, Self, and Purity”)

常楽我浄

9 of 15

Calligraphy, hanging scrollDimensions: 133 x 33.4 cmCa. 1963These four characters represent the “four merits” or qualities of nirvana that are highlighted in the Nirvana Sutra. The term speaks of the state of enlightenment—realizing within one’s heart an ever joyful and pure self able to disengage from ego. It is also described as having constancy, serenity unswayed by emotions good or bad, absolute freedom, and clarity that sees beyond false views and superficial distinctions. Shinjo earnestly wanted to help people realize “Permanence, Bliss, Self, and Purity.” This is perhaps why such vigor infuses both the shape of the characters and his brush movements, while the work as a whole expresses harmony and balance.

Horyu Kuon (“Eternal is the Dharma Stream”)

法流久遠

10 of 15

Calligraphy on shikishi poem paperDimensions: 27.3 x 24.3 cmFrom the richly drawn character ho (top right) to the distinctive signature,this example of Shinjo’s calligraphy reveals a typical sharpness and clarity. The work communicates a definitive sense of peace, with the characters optimally balanced within the white areas.

Jo Raku Ga Jo (“Permanence, Bliss, Self, and Purity”)

常楽我浄

11 of 15

Calligraphy on shikishi poem paperDimensions: 27.2 x 24.2 cmCa. 1963Through its powerful brush movements and thick strokes, this calligraphy projects strength. Yet the controlled nature of the more compact strokes neutralizes any potential heaviness. The artist’s signature also resonates with the main text, unifying the work with a satisfying degree of completeness and resolution.

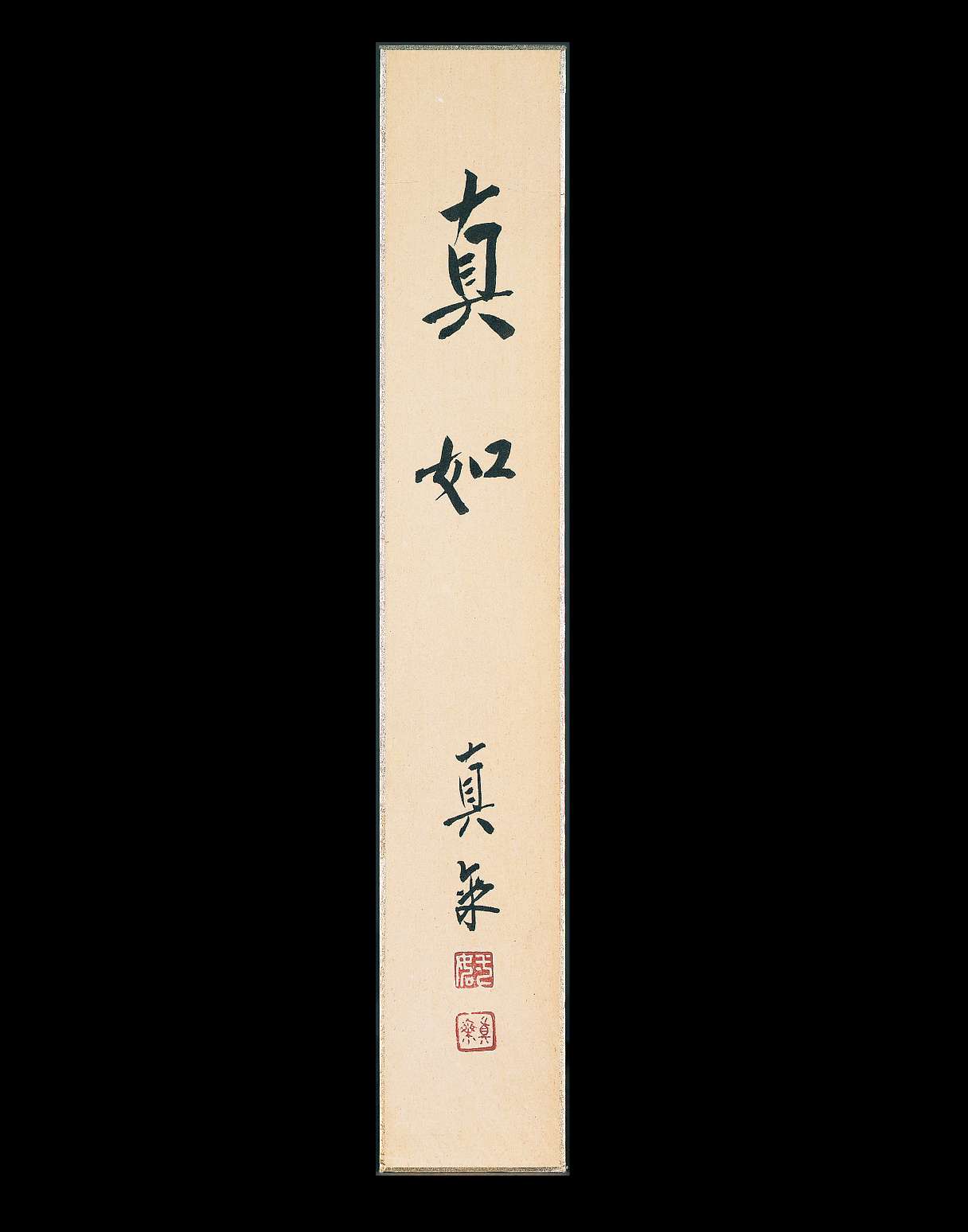

Shinnyo (“Ultimate Reality”)

真如

12 of 15

Calligraphy on tanzaku poem paperDimensions: 36.2 x 6 cmDespite the fact that this work consists of just two characters, it exudes a subtle charm in the pliant give-and-take of the brushwork, and the balanced stroke placement. Although Shinjo never formally studied calligraphy, he gradually developed an effective method of working in the medium. He would first consider what he wanted to write and then contemplate the resonance of the words and characters before finally choosing a style that best suited his objective. As a work of art this piece is complete and fresh, with the left element of the second character nyo unifying the component parts into an organic, coherent whole.

Kotobuki (“Felicitations”)

寿

13 of 15

Calligraphy on a folding fanDimensions: 27.2 x 42 cmCa. 1972This calligraphy consists of a single character centered in a folding fan. The broad outline of the upper half is complemented by the lightly brushed lower half, which creates an effective use of the negative space. This is just one of many examples of Shinjo’s calligraphy on fans, poem paper, and other materials, which he produced as gifts.

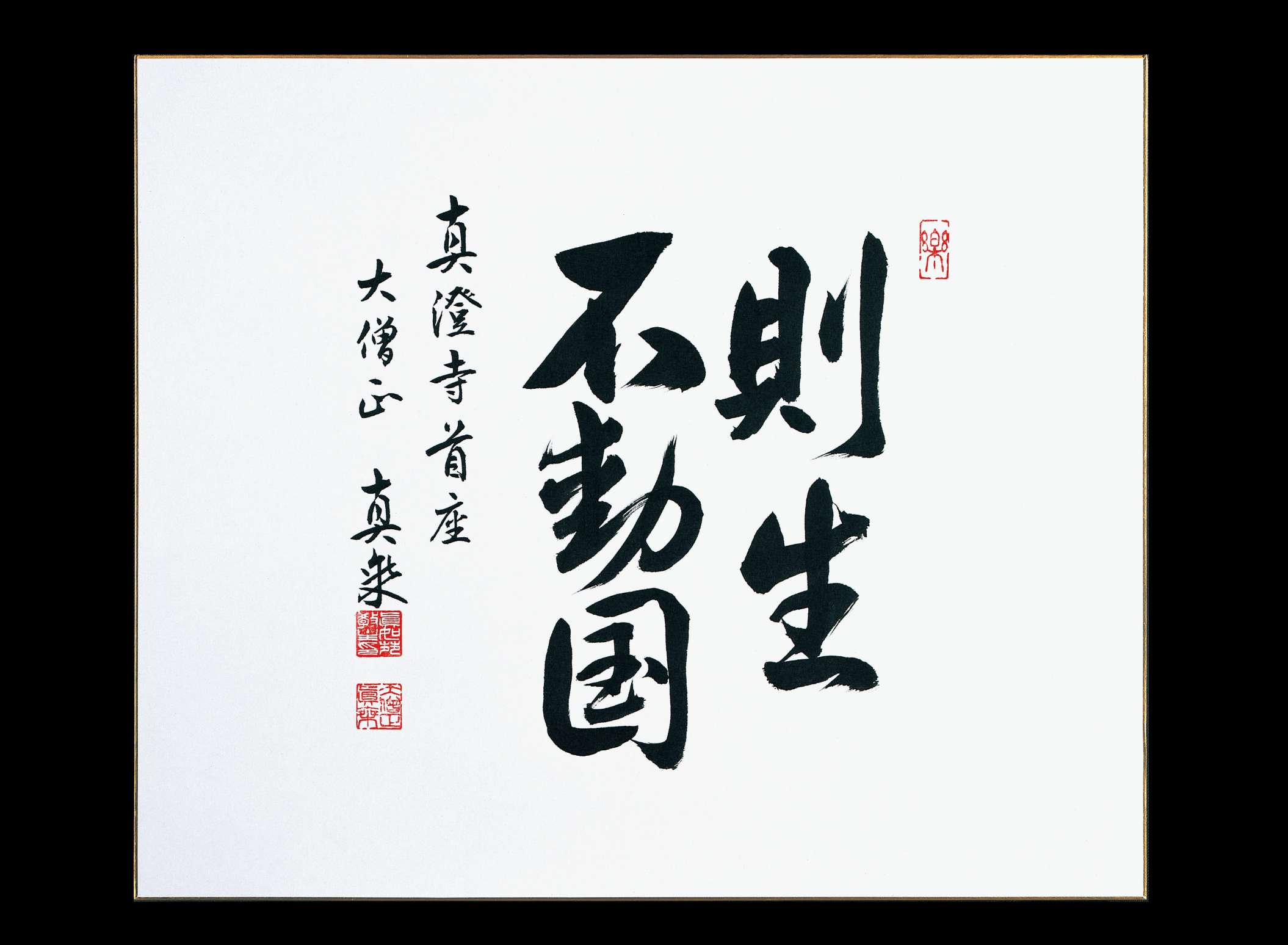

Sokusho Fudo Koku (“Thereupon Born in the Land Immovable”)

則生不動国

14 of 15

Calligraphy on Japanese paperDimensions: 37.7 x 43.5 cmCa. 1978The broad strokes of the character fu (top left) is an important element in this work—contrasting with the delicacy of the lower left character koku.The expression comes from the passage in the Great nirvana Sutra which states: “One who gives priority to making Buddha images and stupas, and takes great joy in doing so, is thereupon born in the Land Immovable (where determination no longer wavers).” Shinjo encountered the passage during extensive study of the Sutra in 1956, and it inspired him to create his original nirvana image.

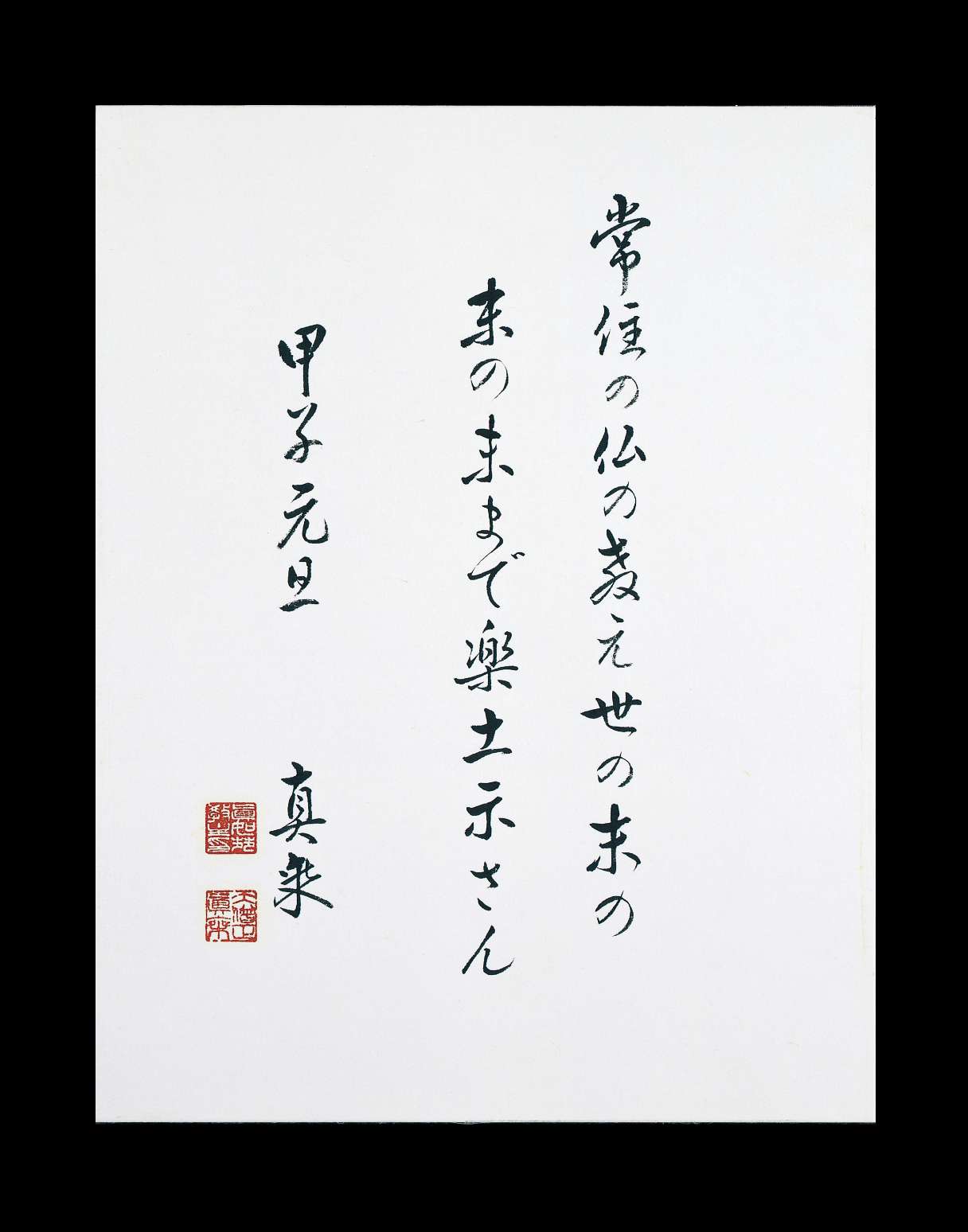

Sonouta Teaching Verse (“Unendingly will the Teachings of theEver-Present Buddha Reveal the Land of Bliss.”)

常住の仏の教え~ (Joju no Hotoke no Oshie~)

15 of 15

Calligraphy on Japanese paperDimensions: 40 x 31cmCa. 1984Shinjo wrote many short teaching poems, or sonouta, as an aid for explaining the more difficult and intangible Buddhist concepts. This particular verse refers to the concept of the “eternal Buddha,” meaning that although the physical body of Shakyamuni may have passed away, his teachings and spirit live on. Shinjo regarded this as one of the key principles of the Nirvana Sutra.